Revisiting the Luddites

Craft, Resistance, and a Different Vision of Technology

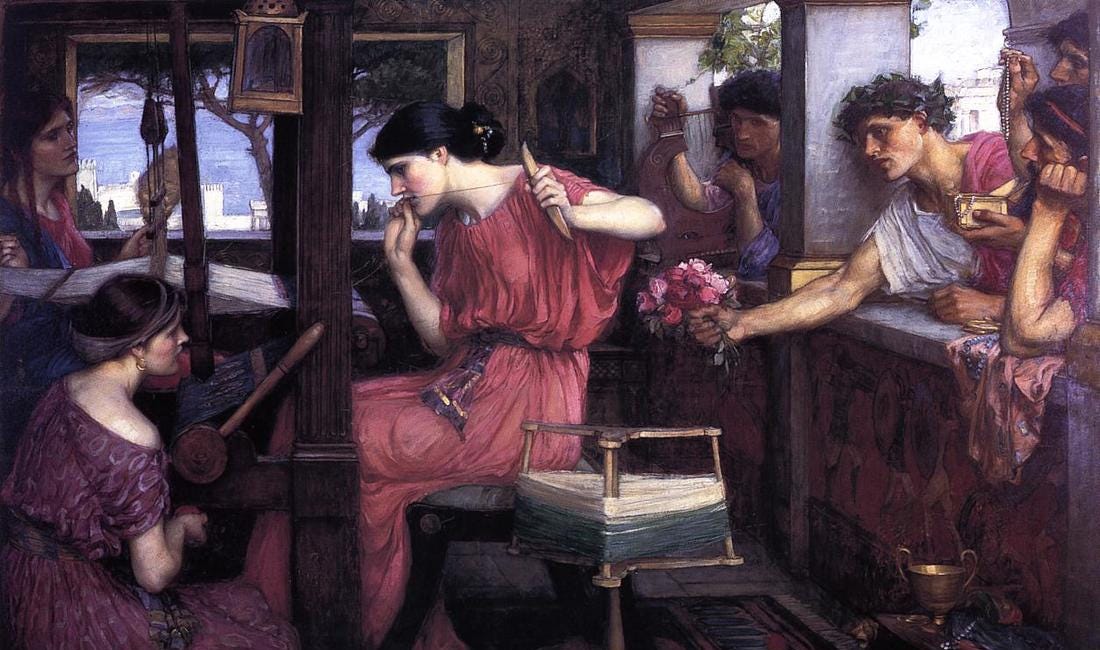

One of the most enduring caricatures in the history of technology is that of the Luddite: a figure driven by blind rage, smashing machines in a futile effort to halt progress. Yet this image, repeatedly used as shorthand for technophobia, obscures the real story of who the Luddites were and what they stood for. Their movement, born in early nineteenth-century England, actually reveals a deep—and in many ways quite modern—critique of how technology can uproot skilled labor, transform communities, and concentrate power in the hands of owners rather than workers. By revisiting the Luddites, we also illuminate how a craft-oriented philosophy of technology intersects with historical realities. We are reminded that human ingenuity in weaving and other domestic arts can be co-opted and centralized, leaving behind cultural traditions, communal ties, and time-honored expertise.

The popular imagination shows Luddites as people so terrified of mechanized looms that they resorted to sabotage. In reality, this monolithic portrayal misses the subtleties that drove skilled textile workers to clandestine nocturnal raids. Historically, many members of Luddite groups were highly proficient artisans—knitters, weavers, and cloth-finishers—long adept at using (and maintaining) complex machinery. Their outrage was not rooted in a blanket rejection of new devices; rather, they attacked the exploitative use of particular machines introduced by factory owners who aimed to de-skill labor, slash wages, and maximize profit. These new factories upended an older ecosystem where artisans, working from home or in small workshops, decided their own schedules and took pride in creating fine, distinctive fabrics.

For many centuries, weaving had been a domestic or semi-domestic endeavor. Skilled workers managed the entire process: preparing yarn, setting up looms, and weaving intricate patterns that came to embody local culture and personal flair. These craftspeople shared knowledge through family, apprenticeships, and artisan guilds. It was a gradual, collective process similar to how a weaving myth like Penelope’s or Arachne’s unfolds—deeply rooted in place, shaped by communal feedback, and open to subtle creativity or changes in design.

Crafting a New Philosophy of Technology: Penelope's Wisdom

For too long, our thinking about technology has been haunted by the specters of Prometheus and Frankenstein. These myths, with their emphasis on transgression, hubris, and punishment, have shaped a philosophy of technology preoccupied with control, disruption, and the dangers of overreach. But what if we began instead with Penelope, the legendary queen …

When the industrial age burst onto the scene, a new rhythm took hold. Mills harnessed water or steam power to operate large mechanical looms. Where local spinners and weavers once controlled their own craft, owners of factories quickly centralized production, forcing many artisans into regimented factory labor. The new machines, driven by a forging-like determination to maximize output, erased the weaver’s autonomy and shrank a once-rich skillset into a narrower set of tasks. In effect, weaving was no longer a holistic, knowledge-intensive craft but a set of mechanical operations bound to time-clocks and overseers.

Luddite uprisings, therefore, were responses to a profound loss of place, identity, and shared culture. In that sense, the Luddites’ story has strong affinities with the weaving tradition described in myths such as Penelope’s loom or the Fates’ threads. We find the same emphasis on continuity, on the role of a collective or local community, and on a sense that technology should respect human dignity. Rather than a violent outburst of ignorance, the Luddites’ frame-smashing was a last resort to preserve a life-world being torn apart in the name of efficiency and profit.

In our contemporary moment, we often draw a bright line between forging and weaving. Forging myths champion acts of control, mastery, and irreversible creation. We see these ideals in everything from corporate mantras extolling “disruptive innovation” to glorified images of lone inventors revolutionizing society in a single hammer blow. Weaving myths, by contrast, highlight iterative, communal processes subject to reworking or gentle unraveling when circumstances demand. The Luddite story offers a real-life instance where an older, weaving-based form of production—domestic crafts, local skill, family tradition—collided head-on with a forging-oriented industrial order.

Though popular narratives suggest that the Luddites wanted to roll back the clock on technology, historical evidence shows many were not anti-machinery in principle. Instead, they insisted that adopting new technology ought to be done in ways that preserved fair wages, respected human skill, and allowed some voice for those affected by the change. Their demands for community control or, at the very least, community input echo a central tenet of any craft-based philosophy of technology: that tools should be oriented toward human flourishing, not simply top-down directives of efficiency and profit.

This perspective resonates with Penelope’s cunning unraveling and re-weaving of her loom. In the Odyssey, Penelope does not reject weaving itself; she transforms its function to meet her needs. Likewise, the Luddites did not reject looms as such; they objected to a new system of production that robbed them of autonomy. A subtle but powerful parallel emerges here: weaving is neither purely technical nor purely symbolic. It is a communal, iterative process where each new row builds on the previous one. Industrial forging, by contrast, can feel like a sudden, decisive blow—imposing forms onto materials without room for revision.

The Luddite movement reveals how technology is not neutral. The same apparatus can be liberatory in one context and exploitative in another, depending on who decides how, why, and when it will be used. History shows that by controlling machines, factory owners exerted leverage over entire communities, shaping wages, daily life, and social organization. This is precisely the kind of top-down forging many of our weaving myths caution against: a triumph of force where those on the receiving end have little recourse but sabotage when reasoned negotiation fails.

Present-day echoes of Luddite concerns appear in debates over the gig economy, data surveillance, or AI-driven automation. Critics who question whether Big Tech or platform capitalism aligns with the common good are often labeled “Luddite” in a pejorative sense. Yet these critiques, in spirit, resemble the original Luddite aim to ensure that technological advances remain a shared benefit rather than a method for consolidating wealth or undermining communal life. Luddite-inspired questions—Who benefits from this innovation? Which communities are harmed or excluded? Is there a path for collective input or resistance?—are as relevant now as they were in the Midlands of England over two centuries ago.

Seeing the Luddites in this more nuanced light underscores the insight that weaving-based technologies cannot simply be replaced by forging-based systems without social consequences. The current pushback against exploitative tech might not always involve literal frame-smashing, but the spirit of protecting human skill, relationships, and well-being from a purely profit-driven application of technology remains alive. Weaving myths, with their emphasis on process and relational subtleties, remind us that resistance can be quiet or outspoken, covert or overt, with the objective not of halting progress but of ensuring it remains genuinely humane.

The idea that Luddites were blindly stuck in the past fails to capture their sophisticated critique. They saw that technology, far from being a monolith, is always embedded in social relations and power structures. By drawing on their example, we recognize that technological adoption is not an all-or-nothing proposition, and that local communities have a moral right to shape and, if necessary, resist the forms that new machinery takes. The Luddite story ultimately amplifies the lessons gleaned from weaving myths. Like Penelope working tirelessly through the night to undo her own day’s labor, communities have the agency to “unmake” or contest technologies that infringe upon their dignity and culture. That act of unmaking can be subtle, as with Penelope’s quiet unraveling, or overt, as with the Luddites’ sledgehammers. Either way, the deeper message is that technology should be woven thoughtfully into the fabric of our lives, rather than forged abruptly, without heed to the patterns that sustain us.